Uganda

From last mile to last household: How results-based financing reached Uganda’s most excluded

Reaching the furthest behind is not only a question of geography. In Uganda, it’s about overcoming affordability barriers, low purchasing power, weak infrastructure, and lack of trust in unknown technologies. To bring solar power and clean cooking to the most isolated communities, to refugee settlements, and to women who are left out of the market, EnDev kept redesigning its results-based financing (RBF) approach. By rethinking what counts as “remote”, integrating gender targets into commercial incentives, and bringing together the supply and demand sides of the equation, it followed its agenda: leaving no one behind in Uganda’s energy transition.

From Kampala to the last mile

In Uganda, reaching rural households with solar and clean cooking solutions has always been a particular challenge. Many areas are remote, infrastructure is limited, and service provision can be costly. Nevertheless, for more than 15 years EnDev, alongside other partners, has been working to expand access and demonstrate that rural markets can indeed be served sustainably. When more companies launched in the country, they started to serve these remote regions, where 90% or more of households lack electricity access and nearly everyone cooks on open fires.

But only within the past decade did development actors start piloting market-based approaches in refugee communities, where many people rely on inefficient makeshift stoves and lighting and struggle with access, cost, and whether they can or want to pay.

EnDev began exploring how to contribute to energy access in refugee settlements in 2018. It first established energy kiosks in Rhino Camp and Imvepi that sold solar lanterns, improved cookstoves, and services like phone charging to refugees and host community members. Then, in 2020, it aimed to speed things up and create a bigger shift with RBF. This included two key programmes: one for refugee settlements and another for last mile solar products across the country. The programmes provided incentives for companies to reach distant customers with cookstoves and solar home systems, the latter including multi-point lighting, charging ports, radios, and televisions. In total, nine companies took part.

15,000

households with access to improved cookstoves

One of the programmes provided incentives for sales within specific refugee and host communities, motivating companies to reach nearly 15,000 households with improved cookstoves and 4,300 with solar home systems. The other programme line, called the Last Mile RBF, was more advanced: it calculated remoteness bonuses based on each customer’s GPS coordinates in relation to trade centres. The harder to reach, the higher the incentive. To balance repayment risks, the RBF also funded default protection plans that companies could offer their customers. It was a nationwide success, enabling companies – some of which had seldom ventured out of the capital, Kampala – to stretch their operations to 110 of Uganda’s 135 districts, reaching 5,000 households.

A tailored design for each target group

But for many people, being left out isn’t just about where they live – it’s also about what they can afford, whether they have control over decisions, and how easy it is to access products. In many Ugandan refugee settlements and host communities, even the cheapest market-based products remain out of reach. Others, like marginalised women, lack financial autonomy, ownership, and access to distribution networks.

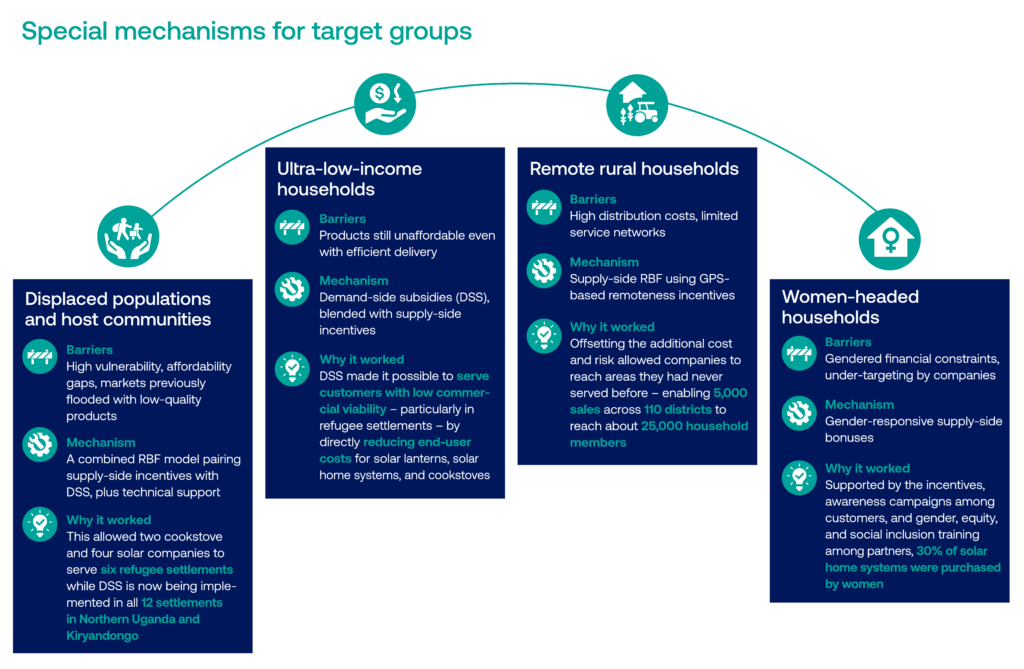

Following the success of the Last Mile Solar RBF, EnDev knew it could work for other people who had been left behind. They identified remaining gaps – in clean cooking, in displaced communities, among marginalised women – and adapted the RBF approach accordingly. Each new iteration started with the same question: who was still left behind? Different groups faced different barriers, so EnDev designed different mechanisms to match them, combining supply-side incentives, affordability support, and gender-responsive targets.

For women-headed households, the RBF included gender targets and reporting requirements, incentivising companies to change not just where, but how and who they sell to. In the refugee settlements, too, reaching people wasn’t the only challenge – affordability also posed a significant barrier. That’s why EnDev introduced demand-side subsidy (DSS), which reduced upfront costs for costumers while maintaining a commercially driven approach. By blending supply-side RBF for companies with demand-side RBF that subsidised consumer prices, settlement residents could be treated as commercially viable customers. Interventions on both sides worked together to help sellers and buyers meet in the middle in these challenging circumstances.

Joining the dots: From single tools to integrated inclusion

But the real shift came when EnDev recognised a pattern: the same mechanisms worked across technologies, and the same gaps remained across markets. That insight became the foundation of a new, integrated approach – one that joined up clean cooking and solar efforts, refugee and gender components, and both supply- and demand-side thinking. EnDev fed those learnings and knowledge into the Worlds Bank’s Energy Access Scale Up Project, which is taking a blended approach for its own RBF, a significant countrywide effort that also includes refugee and host communities.

EnDev’s blended approach not only pooled learning from different markets, it pushed the boundaries of RBF design – proving that reaching the furthest behind is possible when incentives are precise, flexible, and mission-driven. With this, EnDev has kept the private sector’s focus on people, and on the challenges and rewards of reaching them. By tailoring results-based financing to the specific needs of different excluded groups, EnDev enabled Ugandan energy companies to reach places and consumers they never considered possible – people who would have otherwise been left behind.

RBF is meant to incentivise companies to go outside their comfort zones to households that would typically not be attractive. So in our scoping we first ask, why aren’t these looking like reasonable, serviceable segments for these companies?

Helen Kyomugisha, EnDev Uganda Tweet

Key take-aways

When an approach works to reach left-behind populations in one market segment, try it in others – the barriers to overcome are often the same.

Companies want to reach more remote regions and value the opportunity to do so with RBF behind them to justify the added risks.

Supply-side and demand-side RBF, working together, is a strong combination to overcome the most formidable challenges among displaced people.